You’re ready to expand into China. Your legal team has drafted the contracts, your board has approved the budget, and your partners are waiting. Then someone mentions “the Negative List”—and suddenly, your entire market entry strategy is uncertain.

This scenario plays out repeatedly for international businesses attempting to navigate China’s foreign investment landscape. The Foreign Investment Negative List (FIL) functions as China’s gatekeeper, explicitly defining which sectors foreign capital cannot freely enter. Unlike Western regulatory systems that generally allow business activities unless specifically prohibited, China’s approach inverts this logic: if your industry appears on the Negative List, you face restrictions or outright prohibition before you even register your company.

For foreign business owners, expatriates establishing operations, international legal professionals advising clients, and global corporations planning China ventures, understanding the FIL is not optional—it’s the foundation of any viable market entry strategy. Missing a single restriction buried in the List can transform a promising investment into months of regulatory delays, forced partnership structures you didn’t plan for, or complete rejection of your application.

The Negative List operates as China’s primary tool for balancing economic openness with national policy priorities. It doesn’t just regulate; it reveals Beijing’s strategic thinking about industrial development, national security, and economic sovereignty. Reading the List correctly means understanding both what China restricts and why—knowledge that directly impacts how you structure your business, choose your partners, and time your market entry.

Understanding the Structure: Prohibited vs. Restricted Sectors

China’s Foreign Investment Negative List divides controlled sectors into two distinct categories, each carrying different implications for your business structure and operational possibilities.

Prohibited sectors mean exactly what they say: foreign investment is completely banned. These typically involve areas China considers essential to national security, cultural sovereignty, or strategic control. Examples include news organizations, certain telecommunications services, and specific natural resource exploitation. If your core business falls into a prohibited category, no amount of legal structuring, Chinese partnership, or government relations will create a viable path forward. The door is closed.

Restricted sectors operate differently. Here, foreign investment is allowed but subject to specific conditions. These conditions vary significantly and might include mandatory joint venture requirements with Chinese partners, caps on foreign ownership percentage, requirements for Chinese nationals in senior management positions, or special approval processes beyond standard business registration.

The 2024 revision of the Negative List demonstrates China’s gradual opening trajectory. The List has been systematically shortened over recent years, with all manufacturing sector restrictions eliminated entirely—a significant shift for foreign manufacturers considering China production. The latest version removed restrictions in app store services, reflecting China’s evolving approach to digital economy sectors.

Current restricted sectors concentrate in areas China views as sensitive: certain media and cultural industries, critical infrastructure services, specific financial services segments, and industries with direct national security implications. For example, foreign investors in reinsurance services face equity caps, while international shipping agency services require specific operational structures.

Looking forward, signals from Chinese policymakers suggest continued narrowing of restrictions in manufacturing, entertainment, healthcare, and IT sectors. However, the pace and scope of liberalization remain policy decisions that can shift based on geopolitical considerations, domestic economic priorities, and national security concerns. The Negative List is not a static document—it’s a living policy instrument that reflects China’s current strategic calculations.

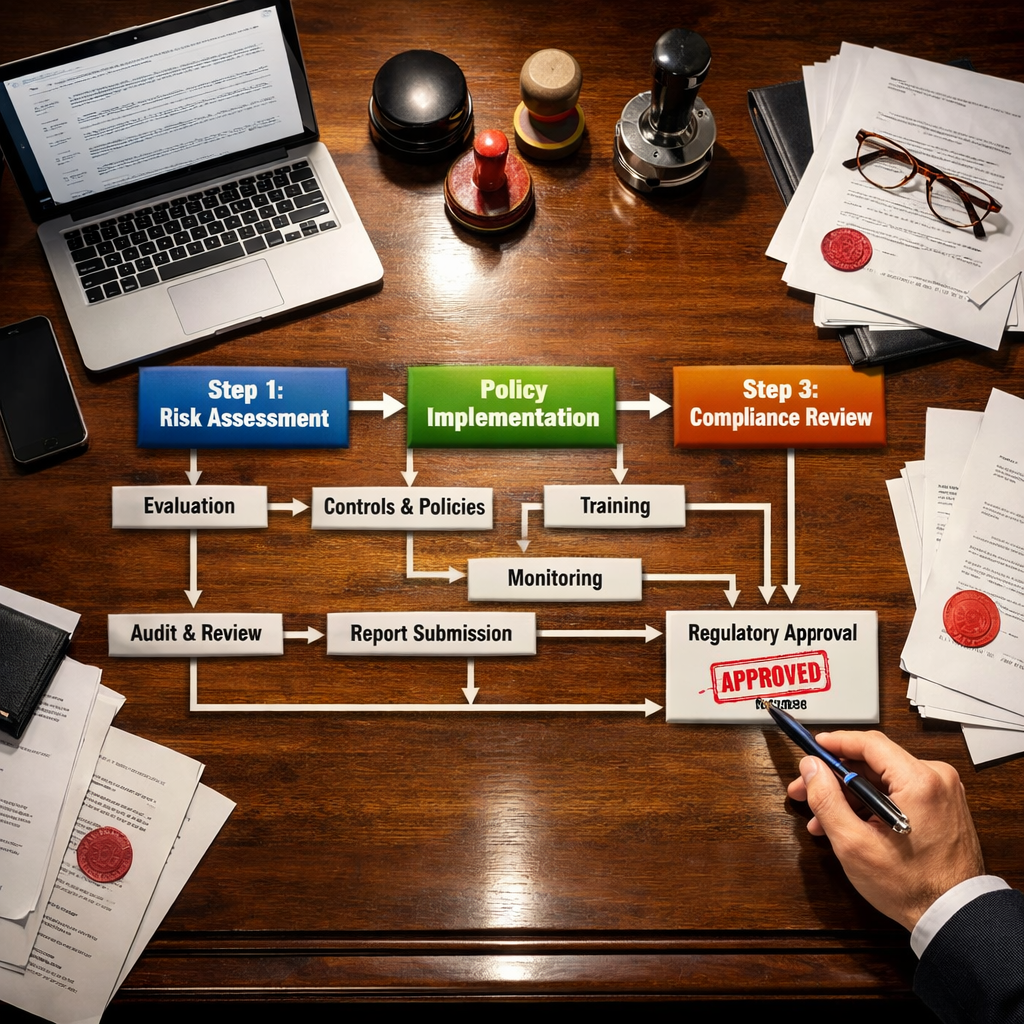

The Three-Step Check Process: Your Practical Navigation Guide

Successfully navigating the Negative List requires a systematic approach. Here’s the three-step process that should precede any major business decision:

Step 1: Identify Your Sector Classification and Restriction Status

Start by precisely defining your business activities using China’s industry classification system. This isn’t always straightforward—Western business categories don’t always map cleanly to Chinese classifications. A “technology consulting firm” in Western terms might span multiple Chinese industry codes depending on specific services offered.

Obtain the current official version of the Foreign Investment Negative List from the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). Don’t rely on summaries, third-party interpretations, or outdated versions. The official text matters because subtle language changes can significantly impact how restrictions apply to your specific situation.

Cross-reference your business activities against every relevant category. Pay particular attention to catch-all language and broadly worded restrictions that might capture activities you didn’t initially consider sensitive. If your business model includes multiple revenue streams or services, check each component separately—one restricted element can complicate your entire structure.

For businesses planning operations in specific regions, verify whether additional local Negative Lists apply. China maintains separate lists for Pilot Free Trade Zones (FTZs) and the Hainan Free Trade Port, which often contain fewer restrictions than the national list. Understanding these regional variations can open strategic location opportunities.

Step 2: Determine Appropriate Business Structure

Once you’ve identified any applicable restrictions, determine what business structure the regulations permit. This decision cascades into everything from capital requirements to operational control.

If your sector appears on the Negative List with ownership caps, you’ll need a joint venture structure rather than a Wholly Foreign-Owned Enterprise (WFOE). This fundamentally changes your business model. You’re no longer operating independently—you’re sharing control, profits, and strategic decision-making with a Chinese partner. The success of your China operations now depends not just on market execution but on partnership dynamics, aligned incentives, and contractual protections in a legal system that may be unfamiliar.

Joint venture requirements force several critical questions: How do you identify and vet reliable partners? What happens if your partner relationship deteriorates? How do you protect intellectual property in a shared operation? What exit mechanisms exist if the venture fails? These aren’t theoretical concerns—they’re operational realities that affect your daily business and long-term success.

For sectors with management requirements—such as mandates for Chinese nationals in CEO or other senior positions—consider whether this aligns with your governance model and risk tolerance. Management restrictions can limit your ability to implement global standards, respond quickly to headquarters directives, or maintain consistent operational practices across your international operations.

Even if your sector isn’t on the Negative List, consider whether regional variations in FTZ lists offer advantages. Establishing operations in an FTZ might provide additional flexibility, faster approval processes, or experimental policies not yet available nationally.

Step 3: Map Required Licenses, Approvals, and Compliance Pathways

Restricted sectors typically require approvals beyond standard business registration. Identify every license, permit, and approval your operations will need, along with the government agencies involved and realistic timelines.

Certain foreign investments require filing with or approval from MOFCOM or provincial commerce departments. Some sectors need national security reviews. Others involve industry-specific regulators like the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) or the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Understanding this regulatory landscape before committing resources prevents expensive surprises mid-process.

Develop a realistic timeline accounting for approval sequences—some permits require obtaining others first. Factor in that government processing times can extend considerably, particularly during policy transition periods or when your business model doesn’t fit neatly into existing approval categories.

Engage legal counsel with specific experience in your sector and recent successful transactions with similar restriction profiles. China’s regulatory environment rewards those who understand not just the written rules but also implementation practices, agency preferences, and practical workarounds within legal boundaries.

Practical Implications: Operating Within and Outside the List

The Negative List creates two distinct operational realities for foreign businesses in China.

For businesses in restricted sectors, expect requirements that directly impact your business model. Joint venture mandates mean sharing control and profits with partners whose interests may not perfectly align with yours. Ownership caps—common in sectors like certain telecommunications or cultural services—limit your financial stake and potentially your strategic control. Management requirements might restrict your ability to install trusted executives or implement global operational standards.

These aren’t merely bureaucratic hurdles—they’re structural constraints that change your business economics. Lower ownership percentages mean smaller profit shares. Mandatory partners require relationship management resources and may demand operational concessions. Management restrictions can slow decision-making and complicate global integration.

However, restrictions don’t automatically mean bad business. Many successful foreign companies operate profitably under restriction frameworks because they understood the constraints before designing their business model. The key is incorporating these realities into your strategy from day one, not discovering them after signing leases and hiring staff.

For businesses outside the Negative List, the principle of “national treatment” theoretically applies—foreign investors receive the same treatment as domestic ones. This sounds liberating, but practical reality is more nuanced.

Even sectors not explicitly restricted face regulatory scrutiny through other mechanisms. Data security reviews under China’s Data Security Law and Personal Information Protection Law apply regardless of Negative List status. National security reviews can be triggered by investments in sensitive technologies even absent explicit restrictions. Antitrust reviews examine competitive impacts. Industry-specific regulations impose operational requirements that may be more stringent than your home market.

Additionally, being off the Negative List today doesn’t guarantee staying off tomorrow. China periodically revises the List based on policy priorities. While the trend has been toward liberalization, restrictions can also be added when policy concerns shift. Companies in sectors near China’s strategic interests should monitor policy signals and maintain contingency plans.

The most successful foreign investors view the Negative List not as a static barrier but as a dynamic signal of where China welcomes foreign capital and where it wants domestic control. Operating in an unrestricted sector doesn’t eliminate compliance obligations—it simply changes their nature and focus.

Risk Considerations and Ongoing Monitoring

The Negative List represents just one layer in China’s multi-tiered foreign investment regulatory framework. Comprehensive risk management requires looking beyond the List itself to related policy instruments and enforcement realities.

Policy monitoring is essential because China’s regulatory landscape evolves continuously. The Negative List gets formal revisions, but related regulations—data security requirements, national security review thresholds, industry-specific rules—change frequently. Government agencies issue implementing regulations and guidance documents that interpret restrictions and create new compliance obligations. What was compliant last year may not be compliant today.

Establish systems to track regulatory developments affecting your sector. Subscribe to official government channels, engage legal counsel with regulatory monitoring capabilities, and participate in industry associations that aggregate compliance intelligence. The cost of missing a significant regulatory change far exceeds the investment in proper monitoring.

Due diligence requires verification, not assumptions. Don’t rely solely on what partners, consultants, or even government officials tell you verbally about restriction status. Obtain written confirmations from competent authorities. For restricted sectors, confirm that your proposed structure meets all requirements before finalizing agreements with partners or committing capital.

When acquiring existing businesses in China, verify that current operations comply with all Negative List requirements. Non-compliant operations may face forced restructuring, penalties, or operation suspension. The fact that a business currently operates doesn’t guarantee it meets current legal requirements—China’s regulatory enforcement has intensified significantly in recent years.

Consider second-order effects of restrictions. If your core business is unrestricted but relies on suppliers in restricted sectors, their operational constraints may indirectly affect your business. If you plan to expand into adjacent services, check whether those activities trigger restrictions even if your initial operations don’t.

The Market Access Negative List, which applies to both domestic and foreign investors, creates another layer of restrictions. While the Foreign Investment Negative List specifically targets foreign capital, the Market Access Negative List applies broadly to all market participants in certain sectors. Understanding the interaction between these two lists prevents costly misunderstandings about what activities your China entity can actually undertake.

Strategic planning should incorporate Negative List realities from the earliest stages. Don’t design a business model that requires unrestricted operations and then discover restrictions mid-planning. Instead, research restriction status before developing detailed plans, so your strategy reflects real operational constraints from the beginning.

For sectors facing restrictions, evaluate whether the China market opportunity justifies accepting those constraints. Sometimes the answer is yes—China’s market size and growth make restrictions acceptable trade-offs. Other times, restrictions fundamentally undermine your business model’s economics or competitive advantages, making China entry unviable or requiring different approaches.

Conclusion: The Negative List as Strategic Guide

China’s Foreign Investment Negative List functions as more than a regulatory barrier—it’s a transparent policy signal showing where China wants foreign participation and where it prioritizes domestic control. Understanding this signal helps foreign investors make informed decisions aligned with China’s industrial policy direction.

The List’s evolution toward greater openness reflects China’s balancing act between attracting foreign capital, technology, and expertise while maintaining control over sectors considered strategically important. This balance shifts over time as China’s economic development stage changes, technological capabilities improve, and geopolitical considerations evolve.

For international businesses, the Negative List should inform but not paralyze decision-making. Restrictions create constraints, but they don’t eliminate opportunities. Many sectors remain fully open to foreign investment. Even restricted sectors can offer viable business models if structured correctly from the start with full understanding of limitations.

The key is approaching China market entry with eyes wide open. Research restriction status before commitment, not after. Structure your business model around real regulatory constraints, not hoped-for exceptions. Build relationships with advisors who understand both the written rules and implementation realities. And maintain flexibility to adjust as China’s regulatory landscape continues evolving.

At iTerms AI Legal Assistant, we help international businesses navigate China’s foreign investment regulations with AI-powered legal intelligence specifically designed for cross-border clarity. Our platform provides real-time guidance on Negative List implications, automatically analyzes your business model against current restrictions, and offers practical structuring recommendations based on your specific situation. Whether you’re evaluating initial market entry, structuring a joint venture, or ensuring ongoing compliance, our China-specific legal expertise helps you make informed decisions with confidence.

The Negative List is not your enemy—it’s your roadmap. Understanding it thoroughly, checking it systematically, and planning around it strategically transforms a potential barrier into actionable intelligence that improves your China market entry decisions. That difference—between viewing restrictions as obstacles versus strategic information—often determines whether foreign ventures in China succeed or fail before they even begin.